Stealing Signs - Issue 16

Investment Memos, Gaming IP, Referral Programs, UpTrust, & Command or Stuff?

Worth Reading

Investment Memos for Twitch & Periscope

Ethan Kurzweil, Bessemer Venture Partners

“it’s helpful to think of Twitch as a marketplace where gamers use the IP of publishers as ‘raw materials’ to make content that viewers want to consume, and charge those viewers through advertising, subscriptions, PPV, and paid HD. Like many marketplace businesses, Twitch creates value for all constituents by allowing them to transact in a low friction environment and handles monetization on their behalf.”

I love getting my hands on VC investment memos, especially for massively successful companies — they are always a goldmine and these two do not disappoint! In this piece, Ethan writes somewhat of a “retro” on Bessemer’s investment in Twitch and Persicope. Above all else, Ethan notes, the the team is critical to ultimate success. He says both of these teams thought about how to reward users and build the right incentives for each stakeholder from the very beginning. I especially liked the note about how each team thought about the fundamental mechanics of social interactions in the offline world and how best to bring those into new media (digital social) — what a crazy time to be an investor (2012)!

I was also surprised to see Twitch described as a marketplace, at least at the beginning. Honestly, I hadn't thought of it as a marketplace before and I had a bit of trouble understanding how it could be considered one, so I broke down two key factors:

Twitch is aggregating supply (streamers) and is the middleman between them and the demand (viewers)

Twitch manages the transaction between the streamers and viewers, and makes the transaction simple and easy

So, maybe it was a marketplace, or, at least, to Ethan’s original point, maybe it was helpful to think of it like a marketplace to understand the outsized potential for network effects. That makes sense to me. I think why I struggled to see this at first is because I didn't quite see #2 — I didn’t think of streamers and viewers as buyers and sellers executing a transaction. Viewers could watch streamers for free early on and a key part of the business model was subscription viewing, not really a marketplace-type transaction. But, Ethan calls out how they monetized viewers over time with Pay-Per-View, thus shifting the viewer<>streamer relationship more to a traditional buyer<>seller relationship in a marketplace, connecting to transact.

Gaming IP is Taking Off in Film & TV

Matthew Ball, VC and former Digital Media Executive

“The degree of audience attachment to and time spent with video games is also without parallel. We don’t hear of regulators and royals warning of ‘Pixar addiction’ or ‘Star Wars obsession’. Tencent and the Chinese government now limit minors to two hours of gameplay per day. Games are also the most effective medium when it comes to the most important storytelling objective: the suspension of disbelief.”

Yet another intriguing piece from Matthew. Since I’m not a movie buff, his overview of the historical disaster gaming IP has been in the film and TV industries was quite interesting. The rest of the piece dives into why gaming IP is now hitting its stride.

There are two important trends here imo: 1. the increasing cultural relevance of gaming, and 2. game studios juicing more out of their IP.

As Matthew notes, gaming has shown a disproportionate ability to create culturally relevant content, IP, and stars. Games foster massive, global fan bases, celebrities amass millions of followers on the back of gaming-related content alone, and games are taking advantage of their ability to digitize the best real world experiences (See: Marshmello’s Fortnite Concert). Gaming has forged a cultural impact on par with film and TV and now the line between them is blurring. Matthew calls out the many cues film and TV have taken from game play experience in the past and that now, video games are becoming a medium through which real stories can be told. I think the line between film and game will only get blurrier over time, and that stories told through video games will be far more compelling than anything we’ve seen on the big screen.

Onto trend number 2, due in part to the cultural shift covered above, the large game studios are finally able to take full advantage of their IP. Much like they’re partnering with smaller game studios to build extension stories of their main games, like the Riot Forge & League of Legends program discussed in Stealing Signs - Issue 13, studios are now working with film studios to extend their gaming universes. Like trend #1, I firmly believe this will become more common over time and that we’ll see many, many game franchises produce film and TV content. I was very surprised to learn that PlayStation is actually taking this matter into their own hands with PlayStation Productions, their attempt at an internal game studio group to adapt its gaming IP. Fascinating. I wonder if they’ll be able to execute. They certainly have the necessary support in Sony Pictures.

Both of these trends have implications for where I think we’ll see investor dollars flow to in the future. Game studios that exhibit the ability to make highly-engaging content will become exponentially valuable as their production abilities potentially shift from just games to both games and short video content over time. Technologies that enable developers to easily build on top of existing IP may also become quite lucrative investments. I’m not sure how partnerships with large studios work today, but my guess is that it takes a lot of effort to onboard a small studio to all of their content, regulations, and digital assets. The large studios could develop these tools themselves, but I think there may be an opportunity to help them more effectively juice their IP.

Facebook’s Most Controversial Growth Tool

Steven Levy, Author of Facebook: The Inside Story

“Zuckerberg believes that by friending your weak ties — which includes people you hardly know — you become closer to them. Facebook might even violate the physics of social interaction by stretching the number of meaningful contacts that people can handle. “There’s this famous Dunbar’s number — humans have the capacity to maintain empathetic relationships with about 150 people,” he says. ‘I think Facebook extends that.’”

This excerpt from Steven’s upcoming book is a fascinating story of how Chamath Palihapitiya helped solve Facebook’s (FB) plateauing growth at 90M users in 2007. In short, he suggested FB’s North Star metric should be Monthly Active Users (MAUs) and recommended that they look at every aspect of FB’s business in light of this metric. To do so, Chamath built the "Growth Circle,” a high-powered, talent-rich, and adversarial team tasked with propelling FB over 100M users and powering future growth.

The most effective, and most controversial, feature they developed was People You May Know (PYMK), which they took from LinkedIn. This feature showed users people that weren’t their friends but were somehow connected to them, with the goal of solving one of FB’s biggest problems: a user was likely to abandon the service if they didn’t quickly connect with 7 friends. PYMK was in large part seen as controversial because it seemed the algorithm driving these recommendations was too good. There were many cases of unwelcome connection suggestions which called into question the ‘above boardness’ of the algorithm and raised some privacy concerns. Apparently, Chamath recently indicated that FB collected data from people that were non-users to create “shadow profiles” and collected data from users that the users did not willingly give to FB, which the Growth Circle leveraged to figure out optimal candidates for the PYMK suggestions. Some of these tactics prompted FB’s chief of privacy to implement rules against using this data and other questionable tactics to increase MAUs.

There were other concerns about the quality of friends suggested from this feature, too, mainly that the algorithm prioritized retention over user experience. Mark Zuckerberg justified this with the idea that FB is not a single-player game, and that the health of the network is more important than any individual’s experience. So, weak connections that don’t create a ton of value for individual users are essentially a community tax to fuel the health of the overall network.

The PYMK feature was insanely successful, but the Growth Circle and Chamath caused a lot of trouble along the way. Many FB employees, including executives, pushed back on the PYMK feature and questioned the Growth Circle’s tactics, but in response often received a “go f**k yourself” from Chamath. This is a great example of how poor company culture, however isolated, can be reflected in the product or service offering. Chamath yelled frequently and had a win at all costs mindset, which translated to insidious user acquisition tactics and compromised user experience.

Lastly, the other key initiative the Growth Circle executed was investment in search engine optimization (SEO) to raise the visibility of FB profiles on Google Search. I was quite surprised to hear this given they had 90M users, although they experienced pretty massive viral growth after opening FB up to the general public, so maybe it never even occurred to them. They likely got thousands of new users a day, entirely organically before plateauing at the 90M mark, thus prompting an investigation into growth tactics.

Building a Referrals Program

Lenny Rachitsky, Entrepreneur & former Product Lead @ Airbnb

“Who should invest in a referral program?

Businesses [whose] users know a lot of other potential users: Airbnb hosts know other folks with homes, and Dropbox users have friends who would love cheap cloud storage. On the other hand, a head of HR may not know a ton of other heads of HR. Referral programs are most effective when your customers are consumers or small business owners (not enterprises).”

This is an excellent breakdown of what a referral program is and why they’re critical to a marketplace’s success. The most compelling evidence in favor of building a solid referral program comes from some of Lenny’s marketplace research, where he found referrals were the second most common early growth lever for supply and up to 50% of new user growth can come from the program. My experience certainly reflects the significant impact of referral programs found in his research — it’s often an early feature of successful marketplaces I’ve seen and, as Lenny mentions, the programs don’t require a large team to build or operate — he did so with just three people at Airbnb. He actually outlines how they built the Airbnb referral program, too, and includes quite a bit of detail about how it all works — it’s very interesting!

I think a lot about how to build and sustain a successful marketplace business, and a referral program is very high on the list of key features. In fact, for many businesses it’s critical, especially those who have strong word-of-mouth growth, a tight-knight community of supply or demand, and when the service requires a lot of trust to use, as Lenny notes, like staying in stranger’s home does (Airbnb). I’m very interested in exploring what the right incentives are to offer in a referral program. Lenny suggests that cash is not always the right incentive, so I’m curious to hear about successful referral programs and how they got creative with their offerings. I’d imagine cash is most often king, but even if it is the most desirable offer, could non-monetary rewards drive more loyal user behavior for the business? I think it might.

Please reach out if you’re building a marketplace business or have experimented with referral program incentives! I’d love to chat.

<stuff> Weekly!

LOL Weekly: Mic’d Up

lol. Kris Bryant and Anthony Rizzo, two of the Chicago Cub’s top players, were asked to wear microphones for a recent Spring Training game and were interviewed during their at-bats and in the field. It was so, so good. Bryant does a reenactment of Henry Rowengartner from Rookie of the Year and Rizzo asks someone to “bang for him” while he’s in the batter’s box in reference to the Astro’s sign-stealing scandal where players would bang on trash cans in the dugout to indicate to the hitter which pitch was coming.

The in-game player acknowledgements of this scandal have produced my favorite moments of Spring Training by far. Trevor Bauer, a pitcher for the Reds, told hitters which pitch he was throwing for an entire inning, essentially in protest of the scandal and punishment the Astros’ received. This stuff is probably unnecessary, but I’m glad to see players stick up for themselves and the integrity of the system. Plus it’s pretty funny.

Funding Weekly: UpTrust

“Uptrust provides a tech platform which ensures people attend mandatory appointments in the criminal justice system by reminding them of their obligations and connecting them to relevant social services. With the new app, clients will be able to message multiple stakeholders (such as their attorney and social worker) and learn about local opportunities such as free or reduced transportation to court and expungement clinics.”

Pretty cool. Uptrust received $1.3M in funding from Schmidt Futures, Inherent Group, and Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation.

It appears this industry suffers from a common problem in healthcare industry: resources awareness and accessibility. I’m always glad to see entrepreneurs leverage technology to solve problems in overlooked industries with overlooked user groups. Excited to keep track of this one.

Baseball Weekly: Command or Stuff?

Eno Sarris, The Athletic

“The pitch that was most stuff-dependent in our analysis was the changeup (64 percent of the importance came from the stuff metric). Stuff, for a changeup, is mostly built on movement and velocity difference off of the fastball, so it’s all intertwined.”

This piece is a fascinating investigation into what’s more important for a MLB pitcher: command, the ability to put pitches in the right places, or stuff, pitches with lots of movement and/or velocity. In my experience, stuff is definitely more important, and Sarris’s research agrees. He and a Data Scientist used a machine learning model with ~7,000 pairs of pitcher command scores and stuff scores as the inputs. The results showed that the relative importance of stuff was larger than the relative importance of command. There’s much more research to be done to validate this (and their model wasn’t very strong in terms of predictive strength) , but it’s an interesting first finding and one that many MLB pitchers agree with, too. All that said, it’s extremely difficult to separate command and stuff — Sarris puts it best:

“Stuff is important! It’s really important. But command also helps explain why your favorite starting pitcher is a starter at all.”

Also, apologies for the paywalled article! If you aren’t already a subscriber to The Athletic, I highly recommend becoming one — they’ve assembled the best roster of sports journalists in the biz and their content is second to none. Eno in particular is a phenomenal writer. Click here to subscribe with my personal link and get 40% off — that’s just $2.99/month!!

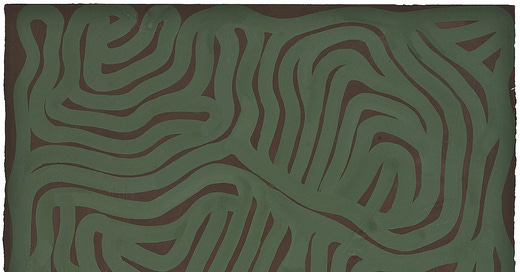

Art Weekly - Parallel Curves (2000)

Sol LeWitt