Stealing Signs - Issue 40

Instagram's Mid-Life Crisis, Conviction Investing, Future of Grocery Delivery, How MLB's Tech Team Built the Future of TV, & Statuettes

Worth Reading

Instagram’s Mid-Life Crisis

Rex Woodbury, Growth @ Airtable

Instead of trying to shift its ethos to fit where the consumer social world is going, Instagram should lean in to what it does best. Instagram isn’t a creator platform. It should build for influencers, not creators.

Aspirational, curated content is a natural fit for commerce, and Instagram has an opportunity to be the destination for discovery-driven commerce. Instagram should stop trying to be TikTok and start trying to be Shopify.

Instagram was built for the influencer, not the creator, so their recent launch of Reels, a copy of the most popular creator tool, TikTok, is curious. Rex notes that Insta got it’s start as a filtered version of reality, which is why it became the perfect tool for influencers looking to flaunt extravagant lifestyles and promote luxury products. Rex suggests these dynamics are closely aligned with the optimal dynamics in eCommerce — personalized recommendations delivered in a compelling, visual format. So, instead of Instagram going after TikTok and building for creators, Instagram should go after eCommerce and continue building for influencers. Be more like Shopify than TikTok — a commerce tool.

A key feature of Instagram is discovery — either via ads in a users feed or the discover tab where users can find new people, products, and companies aligned with their interests and existing follower graph. These discovery dynamics, though, are missing in eCommerce. Take Amazon, for example. Their eCommerce experience is heavily search-driven which is a high friction for consumers and limits the new products consumers interact with. Instagram can leverage their exiting discovery mechanisms in eCommerce to create discovery-driven commerce, which creates a distinctly different user experience from Amazon and the other eCommerce giants. Discovery-driven commerce is much lower friction than search-driven commerce and gives brands a much greater chance of being discovered and a cheaper, more efficient method of reaching consumers.

One issue, though, for Instagram’s search-driven commerce play lays in the evolution of discovery mechanisms in social products. Much like Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat, Instagram is reliant on the follower graph — in other words, users only see content from the people they follow (for the most part). On the other hand, TikTok is based on algorithmic discovery, which means an algorithm decides which content is shown in a user’s feed and that any user can see any content posted on TikTok, not just from the users they follow. It’s becoming clearer that algorithmic discovery is the optimal discovery mechanism for users, not the follower graph, because it provides creators a much broader reach and consumers the potential for more variety. This dynamic is ideal for brands — why settle for limited reach when they could have nearly infinite reach on a platform? Commitment to the follower graph will hinder Instagram’s discovery-driven commerce opportunities — they must detach their product from the follower graph and evolve to an algorithmic discovery-driven product to capture a significant chunk of the eCommerce opportunity.

Conviction Investing

Nicholas Chirls, Partner @ Notation Capital

For starters, it’s simply not easy to tell another fellow investor, a friend, maybe even someone you respect deeply (and believe is good at what they do), that they’re wrong. What if John Doerr came to you with what he believed was an amazing investment opportunity? How might you feel if an entrepreneur explains that her round is oversubscribed, investors you know and respect are committed, and that she might be able to find a little room to squeeze you in? Could you look at these opportunities and entrepreneurs without positive bias?

Who else is investing? A question asked by nearly every venture investor, especially young investors. It’s a gauge on the legitimacy of the deal, which, good or bad, is often a substitute for individual investor conviction in a company. After all, VC is built on networks and relationships, so it’s logical for investors to ask around to see which of their colleagues and friends are interested in a company.

Many investors work to eliminate this question from their vocabulary, though, because there’s little evidence that social proof is correlated with company performance or investor returns. However, it’s often a tool used by young and inexperienced investors to identify hot deals because the alternative, the contrarian approach, isn’t as “effective” in the near term. In fact, the incentive structure in venture capital encourages young investors to ask this question. Time horizons in VC are so long that a truly contrarian strategy, one not informed in any capacity by the question “who else is investing,” doesn’t demonstrate near term success. The contrarian approach results in a portfolio of investments in which other investors see little value (until, of course, a company succeeds), where as the “who else is investing” approach at least has shared value. It’s a meaningful struggle for young investors.

I want to analyze two venture capital investment strategies through the lens of conviction investing: The Specialist and The Generalist.

The Specialist. One may argue conviction investing lends itself to specialist investors. The investor can refine their focus to industries, products, and technologies, which they understand deeply and are uniquely positioned to evaluate. Theoretically, this approach makes conviction investing much easier.

The Generalist. One may argue generalist investing is less conducive to conviction investing because it’s more likely the investor does not have strong conviction in specific technologies or or industries, so are more reliant on 3rd parties. Though, this is why I think many generalist firms, esp early stage firms, put so much weight in the founders — can reach conviction with people if not the industry/technology/product.

I’d love to hear from other investors about how they navigated this dilemma early their career.

Is the best approach to specialize early on?

How did you begin to develop conviction, or a contrarian strategy? Did you ever?

Does the “who else is investing” strategy work?

How did experienced investors react to the “who else is investing” strategy if you leveraged that strategy?

Who are the best “conviction investors” out there?

Grocery Delivery & The Future of Packaged Food

Nikhil Basu Trivedi, Next Big Thing

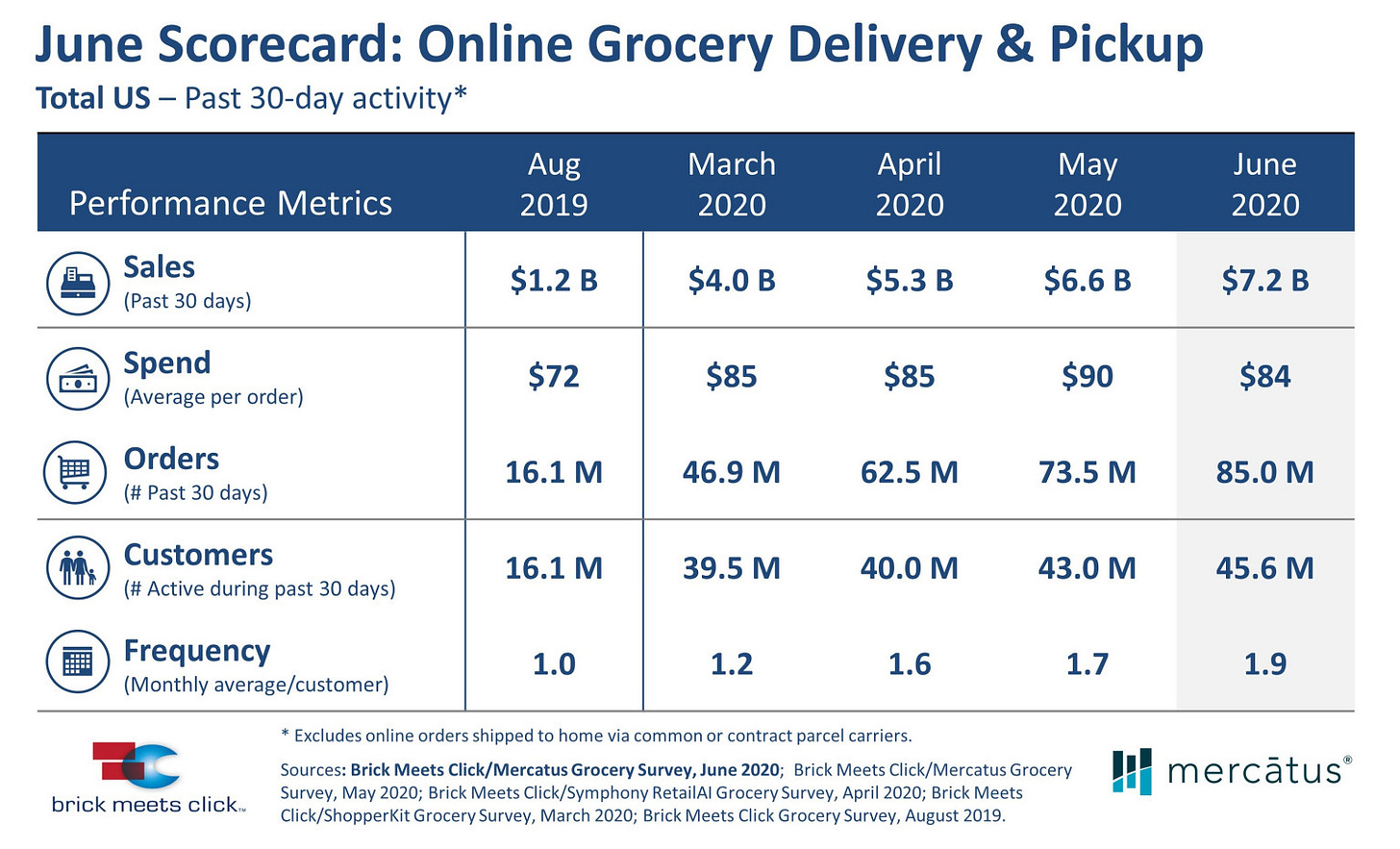

If households that had previously used ecommerce for just one out of every 10 grocery trips were to permanently shift to one out of every five, the long-term impact would be profound. When looking at total US retail sales, food and beverage is a $1 trillion category. If the ecommerce category penetration went from 3.2% to 5.2% over the next couple of years, that’s about $20 billion moving online.

Grocery is having a moment, indeed. The pandemic has forced nearly everyone indoors and shuttered 40% of restaurants in the U.S. by May, causing the eCommerce revolution to finally swallow food and beverage.

While some consumers may migrate back to grocery stores when COVID is through, my guess is that online grocery shopping is here to stay, so much so that online grocery spend will surpass in-store spend in the next 10 years.

The mass migration to buying groceries online presents a massive opportunity not just for the incumbent grocers, but for a new entrant focused on specialization. The endless aisles of Amazon and the newly revamped incumbent eCommerce sites give consumers access to any and every product, all in one place — the same advantage they rely on in brick-and-mortar. However, the internet erodes incumbents’ market power and scale advantages because consumers have infinite choices. Incumbent eCommerce sites are too closely tied to their brick-and-mortar model and lack key value propositions enabled by the internet like curation and personalization. This means new upstarts building curated and personalized eCommerce experiences may win out over the incumbents in non-commodity goods because consumers no longer are incentivized to purchase all grocery items in one place, like they are in the brick-and-mortar model. The internet enables seamless switching between retailers, and, historically, these dynamics tee up offerings focused on consumer experience, not the everything stores.

How Baseball’s Tech Team Built the Future of TV

Ben Popper, The Verge

The group they assembled wasn’t a Silicon Valley dream team, more like tech’s version of Bad News Bears: a minor league beat writer, a former state treasurer, and assorted AV nerds from around the league. This was the height of the dot-com boom, and excitement about the internet was at an all-time high. Right out of the gate, BAM decided to pay a fancy consulting firm a huge chunk of its annual budget to help it create the MLB.com website. Unfortunately the website barely worked. BAM had to scrap it and start from scratch. It was a painful lesson. From then on, BAM would build its own tech.

BAMTech is one of my favorite stories in tech — they delivered video streaming to the masses 3 years before YouTube launched:

“Before anyone else was even thinking about these issues, BAM figured out compression, geofencing, and multi-application delivery at scale," says Rick Heitzman, a venture capitalist who has worked with BAM over the years.

Insane.

Not only did BAMTech build the first infrastructure for video streaming, but it’s one of the best examples of successful corporate innovation in recent memory. The MLB was a near perfect steward of the internal startup that would become BAMTech as they 1. quickly realized the need to spin out BAMTech from MLB, 2. Allowed BAMTech to work with competitors, and 3. Allowed BAMTech to compete against MLB’s clients.

BAMTech Spin Out. A combination of technical challenges and realization of the potential scale and significance of BAMTech’s technology justified the spin out from MLB. While inside MLB, BAMTech was unable to offer employees equity in the business or easily raise outside capital to fund capital intensive initiatives. Thus, they lost out on high-quality tech talent to the major Silicon Valley tech firms. This was a severe disadvantage for a company that needed employees more suited for Google and Facebook than MLB operations.

MLB’s foresight and commitment to the startup mentality is pretty impressive, especially relative to corporations of similar size and maturity. This approach allowed BAMTech to develop competitive advantages rarely seen in corporate innovation efforts — speed and cost:

“BAM’s early entrance to the world of streaming video gave it a big advantage in developing technology, but it also gave the group a head start at the process of deploying infrastructure. Great web streaming requires "points of presence" spread across the globe near population centers. For 15 years, BAM has been building out data centers and high-speed fiber connections, forging intimate relationships with the companies that control the guts of the internet… That head start gives BAM a massive advantage in both speed and cost”

Working with competitors. In this case, competitors are other sporting leagues. MLB allowed, even encouraged, BAMTech to work with other leagues. They eventually partnered with the NHL, WWE, and PGA to power the leagues' online video streaming products. It’d have been very easy for MLB to restrict BAMTech to only working with baseball, which likely would have been rationalized as the best decision for MLB’s near term interests. This is a trap many corporations fall victim to — prioritizing strategic or financial gain for the mothership over asset value creation for the internal startup.

Competing with MLB Clients. MLB allowed BAMTech to get into content creation even though it made BAMTech a direct competitor with MLB clients like ESPN and HBO. With the purchase of production and distribution rights for digital content from the NHL and PGA, BAMTech became more than just a platform. They now had control over the content created on their platform, which, according to investor Rich Greenfield of LightShed who worked closely with the BAMTech team, was aligned with the current stage of evolution in content platforms like Netflix. So, while competing with MLB clients likely ruffled feathers at the mothership, it appeared to be the right strategic move for BAMTech.

Lastly, one of my favorite notes about BAMTech — they weren’t just early to video streaming, but early to mobile. By 2006, they had a mobile app with pitch-by-pitch game updates and live radio — a full year before the iPhone launched…

<stuff> Weekly

LOL Weekly: Guide to Investor Twitter

lololol

Funding Weekly: Narrativ

Sure, affiliate links are a common business model, where publishers get a cut of the business that they’re sending to retailers. There are even companies like Skimlinks and VigLink that automate this process.

But Narrativ is doing something a bit different. It turns these links into an advertising unit called a SmartLink, where different retailers can bid in real-time for each click.

Narrativ, a marketplace for unbiased product recommendations, raised a $6M Seed round from Act One Ventures, Tails Capital, and NEA. Narrativ’s solution automatically turns product links into ad units without any extra work by the publisher. Narrativ also enables retailers to bid different amount for different users with varying levels of exposure the brand and product.

This could drastically alter the content consumption on the internet. Narrativ can transform and article into an Instagram-like experience, which I imagine will dramatically improve conversion. It’ll be interesting to see how publishers evolve their content frameworks to account for a visual, contextual ad unit.

Baseball Weekly: Don’t Apologize for Fernando Tatis, Jr. — Embrace Him

Dan Szymborski, FanGraphs

If you follow baseball, you might be aware of the minor scandal “caused” by Fernando Tatis Jr. on Monday night. Without the usual tens of thousands of fans in attendance to serve as direct witnesses, Tatis brazenly and maliciously hit a grand slam of Texas Rangers pitcher Juan Nicasio on a 3-0 count, while fully aware that his team had a seven-run lead. Ian Gibaut then came in and threw behind Manny Machado, sending an important message that acts of baseball will not be tolerated! Despite Chris Woodward’s efforts to explain Tatis’ violations of baseball’s sanctified unwritten rules, MLB had the temerity to give suspensions to Woodward and Gibaut. Rob Manfred may as well have thrown mom’s apple pie off the window sill.

Excellent analysis of Padres phenom Fernando Tatis, Jr. Dan suggests he's a superstar in the making, if not one already, and the numbers back it up. If his rookie campaign where he finished 3rd in NL Rookie of the Year voting after playing just half a season wasn't enough, Tatis, Jr. is off to a white hot start in 2020. Through just 26 games, he leads the league in home runs (12), RBI (29), and is 5th in on-base plus slugging (OPS). He’s on a tear.

Beyond the numbers, though, Fernando Tatis, Jr. should be embraced for his flare and passion for the game — let the kids play. Unwritten rules in baseball should be a thing of the past.

Art Weekly: Statuettes

Julian Opie

Julian Opie's distinctive reductive style draws from diverse influences including billboards, classical portraiture and sculpture, dance, Japanese woodblocks, and cartoons. His work comprises silhouettes, animations, LED animations, and simplified portraits and landscapes (such as Landscape? from 1998-99, a screen print of trees, grass, and sky in a flat pictorial rendering that recalls a child's puzzle). Employing a variety of media and technologies to make "paintings" of his subjects, Opie distills everyday images and experiences into concise but evocative signs and pictograms.